When the Body Mirrors the Mind: The Connection Between EDS, Autism, and Chronic Survival

For years, I thought my exhaustion was laziness, my pain was weakness, and my dizziness was dehydration. I pushed harder, fought longer, and ignored the quiet signals of my body until I couldn’t anymore. It wasn’t weakness — it was Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Autism, and survival. Now I move slower, softer, and more intentionally — not because I’ve given up, but because I’ve finally learned to listen.

© thechronicallyresilient

By Frankie — Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

For most of my life, I lived in survival mode without realizing it. My body was always tight, tense, and unpredictable — pain was constant, fatigue was familiar, and “pushing through” was my default. What I didn’t know back then was that my body wasn’t just tired — it was screaming for understanding.

The Hidden Thread

When I was diagnosed with Autism, ADHD, and Major Neurocognitive Disorder by my neuropsychiatrist who finally saw me as a whole person, something unexpected happened. In the middle of discussing my symptoms, he asked a simple question:

“Are you hypermobile? Do you have stretchy skin?”

No doctor had ever connected those dots with my medical history before. But that question — and the awareness behind it — changed the trajectory of my health. It led to the realization that I also have Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), a connective-tissue disorder that affects collagen throughout the body.

Hypermobile EDS — The Unseen Connection

Unlike other forms of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, hEDS doesn’t yet have a definitive genetic marker. It’s complex, often misunderstood, and dismissed for years as “just joint pain” or “being flexible.” But hEDS is more than that — it’s a systemic condition that affects joints, muscles, skin, and even the nervous system.

New research suggests that hEDS may have immunological roots, linking it closely to the neurodivergent population. Many of us who live with Autism and ADHD also show signs of connective-tissue differences — hypermobility, poor proprioception, and heightened sensory awareness. It’s as if our entire nervous system and connective-tissue matrix are speaking the same overstimulated language.

“My connective tissue is as sensitive as my emotions — both overstretch in the wrong environment.”

The Co-Morbidities They Don’t Warn You About

hEDS rarely comes alone. It brings a whole entourage of conditions that impact every system of the body. For me, that includes:

• POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome): a form of dysautonomia that makes my heart race and blood pressure drop when I stand up. Some days, even showering or walking across the room feels like climbing a mountain.

• Gastroparesis: slow digestion that leaves me nauseated, bloated, and struggling to eat foods that once brought comfort.

• MCAS (Mast Cell Activation Syndrome): my body can overreact to harmless triggers — foods, scents, or temperature changes — causing hives, swelling, or even anaphylaxis without warning.

• Chronic Hypotension: low blood pressure that leaves me dizzy, foggy, and drained.

• Chronic Dehydration: because of how connective-tissue and autonomic dysfunction affect fluid balance, people with EDS often struggle to stay hydrated no matter how much water they drink. Electrolytes help, but the dehydration is physiological — not neglectful.

Each condition on its own is challenging; together, they create a body that’s constantly negotiating stability.

“My autonomic system forgot how to be automatic — so now I have to consciously manage what most people’s bodies do effortlessly.”

When “Just Work Out More” Isn’t the Answer

For most of my life, I thought my exercise intolerance was just me being “out of shape.” I was told to push harder, work out more, drink more water. But the thing is — that wasn’t true.

No matter how hard I tried, my body would crash. I’d get dizzy, lightheaded, nauseated, and overwhelmed by pain that lingered for days afterward. I thought everyone lived that way — constantly sore, constantly exhausted, always pushing through headaches, dizziness, and discomfort. But they don’t.

And yes, dehydration was part of the problem — but not in the way people assumed. For those with EDS and POTS, dehydration isn’t from lack of effort; it’s a symptom of our physiology. Our bodies can’t retain fluids properly, and our blood vessels don’t constrict as they should. No amount of water could fix that.

“I spent decades apologizing for symptoms that were never my fault — I just didn’t have the right language to name them.”

Living in Constant Survival Mode

Chronic pain trains the nervous system to stay on high alert, and autism compounds that hypervigilance. The sensory system doesn’t just process the world differently — it feels it differently. Every sound, texture, or light can amplify pain and fatigue.

That’s why so many autistic and EDS individuals live in a permanent state of fight, flight, or freeze. Our bodies aren’t malfunctioning; they’re overprotecting. When the connective tissue can’t support the body properly, the brain compensates by tightening muscles, increasing stress hormones, and scanning constantly for danger.

It’s survival — not choice.

Managing the Unmanageable

Living with EDS and its co-morbidities means every day is a careful balancing act between pushing and protecting. Healing isn’t passive — it’s an ongoing conversation with my body.

I do aquatic physical therapy two to three times a week when I can, because the water supports my joints while letting me move freely. It’s low-impact but strengthens my muscles and helps my cardiovascular system without triggering a flare. When I’m not in the pool, I aim for light cardio walks of one to three miles and try to lift weights several times per week to maintain muscle tone and joint stability.

These aren’t vanity routines — they’re survival ones. If I stop moving, my joints destabilize. If I overdo it, I crash. So every workout becomes a dialogue: What can my body handle today?

Because of low hunger drive, absent appetite, and chronic nausea, I use an app to track calories to prevent unintentional weight loss. Eating isn’t just about food — it’s structured self-care that keeps me functional.

And I go to therapy every other week, because when you live inside a body that constantly demands negotiation, you need a place to process the emotional weight too. Talking helps me release the guilt, fear, and exhaustion that come with chronic illness.

“Therapy keeps my mind flexible when my body can’t be. Movement keeps my body alive when my mind feels heavy.”

None of this is easy. Some weeks I’m strong; others I’m surviving hour by hour. But each step — in the water, on the trail, or in the therapist’s office — is a reminder that I’m still here, still adapting, still moving forward with purpose.

The Diagnosis That Finally Made Sense

When my neuropsychiatrist mentioned hypermobility, something clicked. I thought about all the sprains, the fatigue, the bruises that appeared out of nowhere, and the deep aches I’d brushed off as “normal.” I thought about how often I felt like my body and brain were out of sync — my mind racing while my body lagged behind, or vice versa.

That single moment of recognition reframed my entire past. It explained the chronic pain, the joint instability, the exhaustion after simple tasks. It even explained why sensory overload felt like physical injury — because in a way, it was. My body and mind were both running emergency protocols, just trying to survive.

“For the first time, I wasn’t broken — I was understood.”

Looking Back with Compassion

I look back now and see how much of my life was shaped by this unseen battle between my connective tissue and my nervous system. The anxiety that doctors misread as psychological was actually physiological. The fatigue that looked like laziness was the cost of existing in a body that never felt safe.

I used to think I was weak for not being able to keep up — now I know I was fighting on multiple fronts. My body was working overtime to hold me together, even as my mind tried to make sense of it all.

Living with the Body and Mind That I Have

Living with hEDS, Autism, ADHD, and Major Neurocognitive Disorder means existing at the crossroads of neurology, genetics, and survival. But it also means I’ve learned to read the language of my body — every ache, every tremor, every flare. They’re messages, not malfunctions.

And now that I finally understand them, I can live with more compassion, more grace, and more intention than ever before.

If this story resonates with you I hope you’ll stick around, follow my journey @thechronicallyresilient.

And as always, Stay Resilient ❤️🩹

When the Wires Cross: Living with Autism, ADHD, and Major Neurocognitive Disorder (Post-Radiation Brain Injury)

There are moments when my brain feels like a tangled set of wires — sparks of clarity flickering between darkened circuits. I may lose words, forget paths I once knew, and fumble through conversation, but I’ve learned that resilience isn’t about restoring what was lost. It’s about finding new ways to illuminate what remains.

© thechronicallyresilient

By Frankie — Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Social Scientist

Living with autism and ADHD is already complex. The constant juggling act between sensory overwhelm, executive dysfunction, and social decoding takes a tremendous amount of invisible effort. But when you add Major Neurocognitive Disorder (MND) — the medical term for dementia — caused by radiation-induced brain injury after Gamma Knife surgery, the wires of my mind don’t just cross — they sometimes go completely dark.

Understanding the Overlap

Autism and ADHD alone make life a constant negotiation between ability and exhaustion. For me, that meant years of masking — forcing myself to appear “normal,” pushing through sensory chaos, scripting conversations, and maintaining an image of competence even when my brain was on fire inside. But when I developed MND, masking became impossible.

Major Neurocognitive Disorder is often associated with aging, but it can happen at any age. It’s essentially dementia, caused by damage to the brain. In my case, it was a delayed consequence of Gamma Knife radiation used to treat a cerebral arteriovenous malformation — a rare tangle of blood vessels in my brain. What saved my life also fundamentally changed it.

Losing the Words — and Pieces of Myself

There are large chunks of my memory that are simply gone. I can’t recall moments that once shaped who I was. I struggle to find words mid-sentence, my thoughts evaporating before I can anchor them. Sometimes I lose track of what I’m saying entirely.

Conversations that used to feel natural now require enormous concentration. I can’t always interpret tone or filter background noise, and complex instructions leave me frozen. I get confused easily, lost in places I used to navigate without thinking. And every time it happens, I feel a pang of grief — not just for what I’ve lost, but for the people who’ve lost the version of me who could once keep everything straight.

“I used to be dependable — now I’m not, but not at any fault of my own.”

Relationships strain under the weight of my limitations. People assume I’m the same because I still sound articulate, but the truth is, I’m holding things together with fragile threads. My brain works differently now, and no amount of willpower can restore what radiation quietly took from me.

When Masking Becomes Impossible

Before MND, I could still mask my autism and ADHD well enough to survive most social situations. I could prepare scripts, hide overstimulation, and push through burnout. Now, I don’t have that luxury.

The fatigue that comes from cognitive impairment strips away every buffer I once relied on. The filters are gone. My patience for superficiality has worn thin. I say what I mean, even when it’s not what others want to hear. Some call that “difficult.” I call it unfiltered honesty.

“Neurodivergence stripped away my camouflage — but maybe it also stripped me down to my truest self.”

The Loneliness of Not Being Believed

Even doctors sometimes don’t believe me. I’ve become too good at masking my symptoms — at performing competence long enough to pass brief assessments. They see a well-spoken, intelligent adult and assume my brain injury couldn’t be “that bad.” But they don’t see the hours afterward when I crash, disoriented and drained from holding it together.

Being autistic already means living in a world that misunderstands your inner experience. Adding cognitive decline to that creates an isolation that’s hard to describe. It’s a loneliness not just of company, but of comprehension.

The Grief and the Grit

There’s deep grief in realizing that the person I was — the one who could multitask, solve problems, and organize chaos — isn’t coming back. But there’s also resilience in learning how to live differently.

I’ve learned to slow down. To rely on visual aids, notes, alarms, and routines. I give myself grace when I lose words mid-sentence. I find peace in smaller victories — remembering an appointment, finishing a task, making it through a conversation without losing my place.

“This isn’t the life I planned, but it’s still a life worth living — one that demands compassion, creativity, and constant adaptation.”

A Call for Understanding

Major Neurocognitive Disorder doesn’t just happen to the elderly. It can affect people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s — people with families, careers, and lives in progress. It deserves the same level of recognition, research, and empathy as any other neurological condition.

We need more awareness of what it means to live with overlapping neurodivergence and acquired cognitive disability — how it shapes communication, relationships, and identity. I may forget details, lose words, or repeat myself, but I never lose my capacity for love, empathy, meaning and understanding.

So I’ll keep telling my story — even when the sentences come slowly, even when the memories fade. Because somewhere out there, another person is quietly wondering if anyone understands what it’s like when your brain no longer functions the way it once did.

And to them, I want to say: I see you. You’re not broken. You’re rebuilding.

If this story resonates with you, follow my journey @thechronicallyresilient.

And as always, Stay Resilient ❤️🩹

The Bullet That Didn’t Kill Him — But Almost Killed Me: A Story of Childhood Trauma, Silence, and Survival

Seventeen years after the accident, I finally harvested my first mule deer doe. Not for sport — but for healing. For the girl who thought she’d never pick up a rifle again, and the woman who learned she could.

By Frankie — Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

⚠️ Trigger Warning: This story discusses a firearm accident, childhood trauma, and references to suicidal thoughts. Reader discretion advised.

Some moments don’t just change you — they grow you up before you know how to be grown.

I was 12 years old the day I stopped being a child.

And it happened in the wide-open sagebrush country of eastern Montana — a place I once loved for its freedom and silence.

A place that would go silent in a whole new way that day.

The First Harvest and the Shot That Shouldn’t Have Happened

“I was walking up on my first buck, full of pride and innocence — within seconds, everything I knew about safety, confidence, and who I thought I was shattered.”

It was my first year hunting, just two years after completing hunter’s safety — which in Montana isn’t just a class; it’s a rite of passage.

I was with my father, grandfather, and brother. We’d split up at first, planning to meet back at a predetermined ridge. I was over the moon — I’d just shot my first mule deer buck. A 4x5. He was beautiful. I was proud. I had arrived.

As I walked up to the animal, I turned to look back — thinking no one was behind me.

I was wrong.

In a split-second that still plays in slow motion in my mind — my rifle suddenly fired.

There was no warning. No conscious pull of the trigger. The sound shattered the sky and hollowed my hearing. My vision darkened. I felt frozen inside a body that had just experienced something I couldn’t comprehend.

When my hearing and sight started to return, they came back in pieces — first the ringing, then the panic, and then my dad’s voice:

“FRANKIE!! FRANK!! START RUNNING! CHASE THAT TRUCK! RUN!!”

His voice wasn't calm. It was pure panic, urgency, and fear.

And it snapped me into action.

A Run for Help — And a Moment I’ll Never Forget

I took off running.

The sage tore at my legs. My lungs seared. I stumbled, fell, got back up. I screamed so hard nothing came out. I just ran until I caught up to a truck, waving my arms, begging it to stop.

The truck finally did.

A tall man with dark hair in a red plaid jacket and hunter’s orange vest jumped out of the cab and ran toward me. I collapsed into his arms, shaking, barely able to breathe.

I somehow managed to say:

“My grandpa — he’s been shot! It was an accident.”

He grabbed his radio instantly and called it in. We were instructed to meet the ambulance on the highway.

My brother and I turned to wait for our dad and grandfather.

And then — I saw them.

The Only Voice That Spoke Truth

My grandfather didn’t collapse where he stood.

He walked half a mile — with a bullet in his abdomen — up to the road where I was waiting by my dad’s Bronco. He was holding his side, pale, sweating, covered in pain and determination.

When he reached me, he didn’t speak at first.

He just handed me his binoculars — the ones the bullet had ricocheted off of, the ones that had saved his life.

Then he laid down on the ground with his head in my lap.

He looked up at me with eyes half-lidded from pain and said:

“I'm tired, Frankie. Don’t let me go to sleep.”

I’ll never forget the weight of him in my lap — or the terror of believing I might lose him right then and there, in my arms, not during a hunt, but because of something I couldn’t even make sense of.

After that, he climbed into my dad’s Bronco, and we drove to meet the waiting ambulance.

He survived.

“I remember the world going silent — and the silence stayed long after the sound of the shot was gone.”

The Silence That Followed

After surgery, I was the first person he wanted to see.

He held my hand and told me:

“This was not your fault. I don’t blame you. I’m not mad.”

I believed him — or tried to.

But no one else said those words.

My grandmother wouldn’t look at me. The adults went quiet. The police questioned me.

And after one brief session with a school therapist, I was deemed “fine.”

I wasn’t fine.

When Trauma Is Treated Like a Fluke

Childhood trauma isn’t just about what happens to you.

It’s about what happens after.

When adults don’t talk to you, don’t help you process, don’t believe you — the wound goes uncleaned.

Unfelt pain doesn’t vanish.

It festers.

It waits.

Growing Up in the Quiet

For years, I replayed that day over and over, trying to make sense of it.

Trying to figure out how the rifle fired.

Trying to understand what I’d done — and why no one was talking about it.

I knew my finger wasn’t on the trigger. I knew I followed the rules. I knew I hadn’t reloaded — and yet I was the one the police pulled aside. I was the one who got quiet stares. I was the one who went silent — because silence seemed safer than saying, “I don’t understand what happened.”

But staying silent came at a cost.

I didn’t just stop being a child that day — I stopped knowing how to be alive in a world that expected me to carry on as if nothing had happened.

I internalized the blame.

I turned the confusion and guilt inward.

I became afraid of myself — afraid of what I’d done, and what I might do.

I was terrified, constantly, that I was capable of causing harm without knowing how or why.

And no one saw it.

No one checked in after the hospital.

No one asked how I was sleeping, or if I was eating.

I withdrew.

I masked.

And as a result — I spiraled.

Nights were the worst. I had vivid nightmares. Terrifying reenactments. Sweaty flashbacks I couldn’t escape from.

And slowly, without language for what I was feeling, the only escape I saw was not being alive anymore.

I was a child silently contemplating death — because I thought that was the only way to escape what I'd allegedly done.

That’s what untreated trauma does — especially to an undiagnosed autistic kid with ADHD living in an abusive home, where feelings weren’t safe and silence was survival.

When you learn that your pain isn’t welcome, you stop showing it.

And when you're never taught how to process the unbearable, it turns inward.

A Question That Changed Everything

Years later, when I was finally diagnosed with PTSD, my psychiatrist asked me something I had never allowed myself to consider:

“Frankie, your father is an alcoholic and you know your finger wasn’t on the trigger. What if your father was the one who accidentally shot your grandfather… and you were made to believe it was you?”

That question changed everything.

It cracked open years of silence and self-blame, forcing me to see the possibility that the story I’d carried might never have been entirely mine to bear. I may never know the full truth — but I know that little girl deserved to be believed, protected, and guided through this.

Instead, she was left to survive the weight of everyone else’s fear.

How I Reclaimed the Wild

I didn’t go back to hunting for fourteen years.

It wasn’t until I met my husband in 2018 that I picked up a rifle again and it would be three more years before I harvested my first deer seen in the picture above

.

With him, hunting became something different — not about ego or perfection, but about connection, sustainability, and healing.

It was the first time I saw hunting as a way to reclaim the parts of myself I’d buried.

To step back into the wild without fear — and with reverence.

Now, even with POTS, brain injury, significant hearing loss and auditory and visueal processing issues, visual impairment, and neuro fatigue — I still go.

Not to prove I’m capable.

But to remind myself that I still belong.

Because the wild didn’t abandon me — people did.

For the Child I Was and the Woman I Am

If I could speak to that 12-year-old girl now, I’d tell her:

You didn’t do anything wrong.

There were layers of things working against you.

You followed the rules.

And the silence that followed wasn’t your fault either.

You didn’t deserve the blame.

You didn’t deserve the shame.

You didn’t deserve to be alone in that pain.

And one day — you’ll find your way back to those sage-covered hills.

Not as the child who fell —

But as the woman who rose.

If this story speaks to anything you’ve carried alone — childhood trauma, chronic illness, neurodivergence, or the long road back to yourself — I hope you’ll stay with me, follow along @thechronicallyresilient.

And as always, Stay Resilient. ❤️🩹

When the Wild Becomes a Mirror: Hunting With a Brain Injury, POTS, and Fading Senses

Hunting with POTS, visual processing issues, and brain injury isn’t just physically demanding — it’s a daily lesson in resilience, adaptation, and honoring your limits.

By Frankie — Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

There’s something about watching the sun crawl across the eastern Montana sky that reminds me I’m still here — still fighting, still learning what this new version of my body can and can’t do.

This year’s antelope hunt wasn’t just about the chase. It was about reckoning — with my body, with my brain, and with the stillness that comes after realizing even the wild doesn’t quiet the storm inside you anymore.

Between the Wind and the Wild: When Your Eyes Aren’t Your Own

“It’s like trying to hold still in an earthquake — my vision feels shaky, like I can’t anchor to the world long enough to aim, to trust my body.”

The rolling hills of eastern Montana are gentle — slow sloping, wind-laced, and dotted with sage — but even walking them feels like scaling a mountain. The moment there’s any incline, my heart rate spikes to nearly 170 bpm. I live with POTS — and the unpredictability of how my body responds means I never fully know if it’s going to cooperate.

And when my heart is pounding, my vision starts to go with it.

My brain can’t focus the way it used to. Objects feel “shaky,” and no matter how much I steady my breathing or brace my rifle, the world won’t hold still. Even spotting an antelope — something I could do in seconds a few years ago — becomes almost impossible through a scope that never stops quivering.

When my heart races, my ability to see declines. But that’s not by accident.

Why Vision and POTS Are Linked

POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome) forces your heart to work overtime just to keep blood circulating, especially when you stand or exert yourself.

When your heart rate skyrockets:

Your body diverts blood from “non-essential” systems (like vision and digestion) to protect vital organs.

Result: Blurry, shaky vision and poor visual focus.

Add in brain-injury-related visual processing issues, and it becomes a full-blown sensory bottleneck.

Losing My Senses, One Step at a Time

“Hunting demands silence. But how do you stay silent when you can’t hear yourself?”

I can’t wear my hearing aids while I hunt — sweat from POTS could fry them, and they’re not waterproof. That means I enter the field unable to fully hear my surroundings.

Every step becomes a gamble:

Am I too loud? Am I missing something? Am I safe?

I rely on my husband, who walks in front of me — his footsteps become my guide, his silence my cue. I use all my energy to keep my eyes on his heels, just trying to stay quiet and balanced in a world that now feels foreign in both sound and sight.

Even speaking becomes complicated. I can’t tell how loud I am, and sometimes I accidentally whisper too loudly — breaking the stillness we’ve worked so hard to create.

“When your body becomes both the barrier and the battleground, even whispering is a test of control.”

The Moment I Knew the Hunt Was Over

We hunted for four days — two trips out per day. I pushed hard, watching the sunrise in awe, enduring windburn on my face and fatigue in open defiance of my symptoms. But on Tuesday morning, as we crested a hill in search of a herd we’d been tracking, it hit me like a wave:

I had nothing left to give.

My brain fogged. Speech processing started crashing. Noise, balance, breathing — every system in my body was begging me to stop. The antelope were still out there, but I wasn’t.

So we called the hunt.

I walked away empty-handed — but not empty-hearted.

This Body Still Belongs Outside

“Grief lives here alongside grit. I hate what I’ve lost. But I love that I still go.”

Hunting isn’t just something I do — it’s something I share. My husband and I rebuilt parts of our relationship in these landscapes. I learned to slow down again, to listen to the wind and let nature carry the weight of what I can no longer hold.

I didn’t grow up thinking “someday my brain injury will affect my ability to aim a rifle,” but here we are. My MRI shows tissue damage and encephalomalacia — silent, structural reminders of what gamma knife surgery cost me. And yet:

I am still here.

I still show up.

I still learn new ways to live.

Because being alive isn’t about bouncing back.

It’s about adapting forward.

The Damage You Can’t See

My MRI shows:

Encephalomalacia and gliosis: Brain tissue damage and scarring from radiation and A/V malformation.

Visual processing issues: From tissue loss in areas related to perception and eye tracking.

Major Neurocognitive Disorder: Diagnosis stemming from these changes.

That’s why I’m starting occupational and speech therapy — to regain even a sliver of control over what’s been lost.

Ending on Purpose

I used to think pushing through pain meant I was strong. That ignoring my limits made me worthy.

Now I know this:

Honoring my limitations is how I stay in the game.

I left the wild empty-handed this time. But I walked away with the kind of pride you can’t hang on a wall — the kind that exists in every breath I didn’t give up, every step I took beside the man who taught me to love hunting again.

I’m not done. I’m just learning how to hunt a different way.

If this resonates with you, and you’d like to follow my journey of neurodivergence, chronic illness, healing, and everyday resilience — you can follow me on social media @thechronicallyresilient

And as always, Stay Resilient ❤️🩹

No One’s Coming to Save You: The Day the Military Broke My Faith

I used to believe in the system — in the promise that if you served with integrity, the military would take care of you. But the day I got sick, everything changed. The uniform that once made me proud became a reminder of how quickly loyalty can be forgotten. No one came to save me — I had to save myself.

By Frankie — Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

I used to believe the Air Force was a family — that when things got hard, when life hit you sideways, your brothers and sisters in uniform would rally around you.

That we’d always take care of our own.

But the day my world crumbled around me, I learned the hard way that the military isn’t a family.

It’s a system.

One that will replace you in an instant, no matter how loyal, hardworking, or dedicated you’ve been.

The Diagnosis That Changed Everything

The day before it all happened, I was diagnosed with an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in my brain — a rare and dangerous tangle of blood vessels that could rupture at any moment. One wrong movement, one bad day, and I could have a hemorrhagic stroke.

I remember sitting with that news, numb.

It felt like there was a bomb in my head, ticking.

I was in shock, unable to process the words “high risk for rupture.”

I didn’t cry. I didn’t even think.

I just froze — hovering somewhere between disbelief and terror.

The next morning, I went into work like I always did.

I was a medic — an Airman in direct patient care, responsible for the health and safety of others.

But as I walked through the clinic, it hit me that I didn’t feel safe taking care of anyone.

I wasn’t even safe in my own body.

I tried to hold it together through my morning patients, smiling like everything was fine — because that’s what we’re trained to do: push through, show up, be mission ready.

But inside, I was falling apart.

When my last patient left, I sat there for a moment, shaking.

I knew I couldn’t keep pretending.

So I did what I thought was right: I texted my NCOIC but not before looking around for him.

I told him something like,

“I’m not doing well, and I don’t think it’s safe for me to see patients or be at work today. I’ve seen all my morning patients, and I have someone who can cover my afternoon ones.”

It wasn’t perfect communication — I could barely form sentences — but it was honest, responsible, and sent before I left.

What I didn’t know was that he wouldn’t see it until later.

The Next Morning

When I walked into work the next day, my NCOIC was in a panic.

He’d just found out that my Flight Commander was trying to charge me with being AWOL and issue an Article 15 for leaving early.

My heart dropped.

I hadn’t done anything wrong — I had followed procedure, covered my patients, and told my supervisor I wasn’t safe to be in patient care.

I had just found out I had a ticking time bomb in my brain.

He wasn’t angry with me — he was overwhelmed by the situation and scrambling to manage the fallout.

But I was devastated.

I tried to explain what had happened — that I had texted him, that I physically and emotionally couldn’t face anyone that day.

I wasn’t defiant; I was in shock.

And still, I was the one being treated like I’d abandoned my duty.

Hearing that I was being accused of dereliction of duty sent me straight into another meltdown.

I left and went to Mental Health immediately.

I was scared, confused, and broken — punished for being human in a moment when I needed compassion the most.

Fighting for Myself

After that, I did what I always do — I fought back the only way I could.

I went to JAG, requested letters of character from the doctors I worked closely with, and gathered every piece of evidence showing my professionalism, reliability, and record.

My NCOIC barely spoke to me after that.

The same people who used to call me dependable, squared away, and trustworthy now treated me like I had failed them.

Eventually, the Article 15 was reduced to a Letter of Reprimand (LOR) — but the damage was already done.

I had never been reprimanded in my entire career.

That single piece of paperwork erased years of service, dedication, and sacrifice.

Because of it, I was later ruled ineligible for my Meritorious Service Award when I was medically retired — just four months after my diagnosis.

Isolation and Double Standards

What cut the deepest wasn’t just the paperwork — it was the hypocrisy.

Around the same time, my Flight Chief received her own life-threatening diagnosis.

Everyone rallied around her.

The unit bent over backward to support her recovery, to make sure she had time and space to heal.

But when I was the one in crisis — when I was fighting to process the fact that I could die at any moment — I was punished.

It was as if because my condition was rare and invisible, it somehow didn’t count.

I wasn’t seen as a person in crisis.

I was seen as an Airman failing to perform.

It broke something in me.

I realized that my worth to the Air Force was measured only by my output — not my humanity, not my service, not my sacrifice.

Just what I could give… until I couldn’t give anymore.

The Aftermath

Within four months, I was medically retired.

I don’t remember much of that time — just flashes of fear, confusion, and grief.

My career was gone.

My reputation as a good medic, a mentor, a leader — gone.

I kept asking myself: What did I do wrong?

All I did was get sick.

All I did was tell the truth.

And yet, I was punished for it.

What I Learned

It took years for me to find peace with what happened.

The truth is, sometimes no one is going to care.

No one is going to fight for you.

No one is coming to save you.

The military will replace you in an instant — but you can’t be replaced at home.

If you ever find yourself feeling used, dismissed, or broken by a system that was supposed to protect you, remember this:

Take care of yourself first.

Your worth isn’t measured by your rank, your performance, or your ability to keep pushing through pain.

I wish I had known that sooner.

Follow My Journey

If this story resonates with you — if you’ve lived through medical trauma, chronic illness, or the invisible fight to be believed — I invite you to walk this path with me.

You can follow my journey and advocacy work on Facebook and Instagram, where I share updates, insights, and reflections on life after survival @thechronicallyresilient

And as always,

Stay Resilient❤️🩹

From Life-Saving Surgery to Lifelong Consequences: My Fight for Answers

I share my story not just for awareness, but for anyone navigating life after Gamma Knife treatment. Brain radiation side effects and rare complications are rarely discussed openly — but they deserve to be. My journey is one of resilience, disability, and medical advocacy.

By Frankie

Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

“I never imagined the treatment that saved my life would take so much from me.”

If you’re here, maybe you’ve been where I’ve been — sitting across from doctors who once saved your life but now can’t explain what’s happening to your body. Maybe you’ve searched for answers in medical portals, scrolled through research articles at 2 a.m., or wondered if anyone would ever believe you again.

This is my story — of survival, loss, and a slow, painful rebirth into a life I never expected to live.

The Diagnosis That Changed Everything

In December 2018, I was diagnosed with a cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) — a rare, tangled web of blood vessels deep in my brain. At the time, I was an active-duty medic in the United States Air Force, thriving in a high-pressure environment where precision and strength were part of my daily life.

When the diagnosis came, it felt like a betrayal by my own body.

I wasn’t the patient — I was the healer, the one others turned to in crisis.

My AVM was too large for open surgery, and on January 31, 2019, I underwent Gamma Knife stereotactic radiosurgery, a targeted form of brain radiation designed to destroy the AVM over time. The doctors were confident. I was told it was safe — precise, effective, controlled.

And it was. Gamma Knife saved my life.

But no one warned me about what else it might take.

“I went from fighting for the lives of others to fighting for my own.”

Within a week, I developed bilateral pulmonary emboli — blood clots in both lungs — triggered by my oral contraception. I survived that too, but my recovery was complicated and frightening.

A year later, my lungs failed me again. After months of shortness of breath and fatigue, I underwent a bronchoscopy and mediastinoscopy. The diagnosis: pulmonary sarcoidosis, a rare autoimmune disease that attacks the lungs and lymph nodes.

I was exhausted — but hopeful. I thought maybe this was just part of the healing process.

I was wrong.

When the World Went Silent

In September 2019, while hunting, I suddenly lost hearing in my left ear. One moment, I was aware of the world — the sound of my breath, my heartbeat and the frost crunching under my boots — and the next, there was silence. I was hiking the rolling hills of eastern Montana chasing antelope with my husband when suddenly there was a high pitched ringing in my left ear followed by that muffled hearing you get after firing a rifle without hearing protection. Except, my hearing never came back…

Eventually, I lost hearing in my right ear too and now I wear hearing aids to accommodate for some of my hearing difficulties.

Doctors couldn’t explain it. They called it idiopathic (no known cause) sudden sensorineural hearing loss, and every test came back inconclusive (allegedly). Actually, initially it was blamed on an extremely rare complication of sarcoidosis, neurosarcoidosis, or sarcoidosis. of the nervous system which can cause sensorineural hearing loss. This didn’t make sense though because my MRIs were not consistent with neurosarcoidosis.

With my medial background I naturally began doing my own research. That’s when I discovered studies linking Gamma Knife radiation to hearing loss and even scarier, cognitive impairment depending on which brain regions were affected. Before ever experiencing cognitive decline I reached out to my neurosurgeon and radiation oncologist through my MyChart portal messaging in December 2019, asking if my hearing loss could be related to my gamma knife surgery, looking for validation of what I already knew to be true.

They didn’t reply in writing. They called instead. I remember the words clearly — “That’s not possible.” My husband remembers the conversation too too.

But I knew something was happening inside my brain.

“It felt like my mind was slipping away, piece by piece.”

By 2021, my cognitive began impacting my life and I didn’t even realize it.

I forgot tasks, misplaced simple information, showed up wrong place wrong time, lost my train of thought mid-sentence.

I had always been sharp — the Air Force medic who thrived under pressure — and suddenly, I couldn’t function. I lost my job as a clinical receptionist, something that had once come naturally to me and theoretically should be super easy given my past profession. It devastated me, embarrassed me, brought about shame and deep unsettling fear for my future.

I wasn’t lazy. I wasn’t unfocused.

I had a brain injury — and no one believed me.

The Diagnoses That Finally Named My Reality

In 2022, I underwent a comprehensive neuropsychiatric evaluation. The results were both validating and devastating:

Major Neurocognitive Disorder

Autism Spectrum Disorder

ADHD

Non-Verbal Learning Disorder

Math Disability

During that same evaluation, the doctor asked a simple question that changed everything:

“Are you flexible?”

I showed him — the bendy joints, the stretchy skin I’d always joked about as a kid. His eyes widened. That led to a referral and, finally, a diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), a genetic connective tissue disorder that explained my whole life — my chronic pain, neurodiversity, fatigue, and joint instability.

“Everything finally had a name — but no one had warned me any of this could happen and even worse they wouldn’t admit it could have happened.”

By 2023, a new MRI confirmed what I already felt: stable but permanent brain damage — areas of encephalomalacia and gliosis, meaning my brain tissue had been injured and scarred. It was described as a “chronic treatment effect.”

The damage is stable.

But it’s irreversible.

In June 2024, after years of monitoring, my AVM had finally shrunk enough to be surgically removed. The resection was successful, but I temporarily lost left-sided vision, which slowly returned after months of recovery as well as more white matter brain damage.

It felt like every victory came with a loss, although I'd do it all over again, to save my life.

Living With the Aftermath

Today, my daily life is a careful balancing act.

I live with permanent cognitive and sensory deficits — and a long list of conditions tied to Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, including:

POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome)

MCAS (Mast Cell Activation Syndrome)

Chronic dehydration and hypotension

Gastroparesis and unintentional weight loss

Chronic pain, fatigue, and insomnia

Spinal instability with bulging discs and synovial cysts

“Every day is survival disguised as routine.”

I rely on structure and technology to function:

AI tools to help me write and remember,

Shared calendars, reminder apps and detailed notes track my days an responsibilities,

and the unwavering support of my husband and mother to help me stay on track and accomplish what I need to day to day.

I undergo IV hydration therapy multiple times a week to manage chronic dehydration, POTS and hypotension.

I carefully monitor my diet and weight just to maintain enough stability to take my ADHD medication safely.

Every aspect of my existence is managed, measured, and monitored.

The Fight for Answers

I have spent years researching, documenting, and trying to understand how my brain — the same one I once trusted to heal and care for others — became the source of my greatest challenges.

When I reached out in 2019, I wasn’t looking to blame anyone. I was scared. I just wanted to understand.

But my questions were dismissed and I was denied timely and thorough diagnosis, treatment and resources that could have made the transition from able to disabled a lot less traumatic. I was made to feel it was “all in my head”, that I was creating stories.

Now, after years of rehabilitation following the triggering of my chronic illnesses, I’m finally strong enough. mentally and physically to ask again and to fight for the truth.

In November 2025, I’ll meet with a neurologist who is willing to review my MRIs and explore the possible connection between my Gamma Knife treatment and my neurological and sensory disabilities.

It will be the first time any doctor has truly taken my concerns seriously.

“Healing doesn’t just mean surviving — it means being heard.”

I’m not seeking sympathy — I’m seeking truth and understanding.

Because I believe every patient deserves to know the full range of possible outcomes before consenting to treatment as well as what their resources are for recovery, support and accommodation if the unthinkable were to happen.

I believe every medical record should reflect a patient’s communication attempts, even when the answers are uncomfortable or are the result of care that was meant to save their life.

And I believe that “rare complications” should still be discussed — not dismissed.

What I Want Every Patient to Know

If you’ve ever been dismissed, told “it’s not possible,” or made to feel like your pain is an inconvenience — please hear me: you are not alone.

Document everything.

Ask questions, even when it makes people uncomfortable.

Request copies of your imaging, lab work, and communications.

And if your instincts tell you something is wrong — trust them.

Because you are the one living in your body.

You are the one carrying its history.

“I am not broken — I am disabled. And I am still here.”

I am forever grateful for the surgery that saved my life. But I wish I had been told the whole story — the possibilities, the risks, and the lifelong adjustments that might follow.

I’ve had to grieve the person I was — the Air Force medic, the quick thinker, the multitasker.

Now, I am someone new: slower, softer, but stronger in ways I never expected.

This is my story — not of loss, but of reclamation.

Of finding strength in limitation.

Of turning silence into testimony.

And if you’ve made it this far, please know — your story matters too.

💬 Follow My Journey

If this story resonates with you — if you’ve lived through medical trauma, chronic illness, or the invisible fight to be believed — I invite you to walk this path with me.

You can follow my journey and advocacy work on Facebook and Instagram, where I share updates, insights, and reflections on life after survival.

➡️ @thechronicallyresilient

And as always, Stay Resilient ❤️🩹

Becoming My Own Chronic Disease Manager: How a Gamma Knife, Pulmonary Embolisms, and a Rare Autoimmune Disease changed everything

When a routine CT scan revealed more than just blood clots, my life changed forever. What began as a life-saving brain procedure led to a cascade of rare conditions — including pulmonary sarcoidosis, a disease that quietly stole my breath and tested every ounce of strength I had left. This is the story of how I went from Air Force medic to chronic disease manager, learning to trust my instincts, advocate fiercely, and find resilience in the spaces where medicine had no clear answers.

By Frankie

Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

Understanding Sarcoidosis — A Rare and Misunderstood Disease

Sarcoidosis is one of those conditions that sounds simple when you first read about it — and yet the more you learn, the more mysterious it really is. It’s a rare autoimmune disease that causes the body to form tiny clumps of inflammatory cells called granulomas in various organs. These granulomas can appear anywhere — most commonly in the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, or eyes — and they can either quietly exist without causing problems or slowly interfere with how those organs function.

What makes sarcoidosis so complex is that no one knows exactly why it happens. It’s believed to be triggered by an abnormal immune response, possibly due to genetics or environmental factors, but there’s no single cause and no single pattern. For some, it’s mild and temporary. For others, it’s chronic, progressive, and life-altering.

Pulmonary sarcoidosis — when it affects the lungs — can cause symptoms like persistent cough, shortness of breath, and fatigue. But sarcoidosis is notorious for masquerading as other diagnoses, because its symptoms are often nonspecific and atypical. Fatigue, shortness of breath, joint pain, rashes, and neurological changes can all be explained by a dozen other conditions. That’s why it often goes undiagnosed for months or years, or is discovered incidentally during imaging for something else entirely.

For me, sarcoidosis entered my story not as a diagnosis I was searching for, but as a hidden thread running through a series of medical crises, ultimately revealing itself after careful observation and follow-up. I wholeheartedly believe that my Gamma Knife radiation surgery on January 31, 2019, acted as a trigger that set in motion a cascade of conditions — from my pulmonary embolisms to sarcoidosis and my hearing loss — amplified or exacerbated by my environmental factors and underlying vulnerabilities.

My Unexpected Diagnosis — When a CT Scan Changed Everything

On January 31, 2019, I had Gamma Knife radiation to treat my arteriovenous malformation — a tangled cluster of blood vessels in my brain that I had lived with for years. It was supposed to be a precise solution to a known problem. But just five days later, on February 5th, I was in the hospital again — this time fighting for my life after developing bilateral pulmonary embolisms. Blood clots had lodged themselves in both of my lungs.

The CT scan that confirmed the embolisms did more than identify the clots. It also revealed something unexpected: bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy — enlarged lymph nodes near the lungs — which raised concerns for pulmonary sarcoidosis. At that time, I was asymptomatic, and with the immediate crisis being my pulmonary embolisms, the finding was labeled “incidental.”

Even then, my instincts kicked in. My background as an Air Force medic gave me a strong understanding of anatomy and pathophysiology, and my autistic special interests — deep dives into research and medicine — had always driven me to dig deeper, to connect dots that others might overlook. I didn’t know it yet, but those instincts would soon become my lifeline.

Because of blood clotting risks, I had to switch from my regular birth control pills to the mini pill — and by July 2019, I was unexpectedly pregnant with our third child. The pregnancy paused everything: no imaging, no biopsies, no follow-up on the incidental CT finding. So I focused on staying healthy and managing my other conditions, knowing that the mystery of the lymph nodes would have to wait.

When I delivered in March 2020, we were discharged from the hospital just one day before the world shut down due to COVID-19. I came home, exhausted and adjusting to life with a newborn — only to develop hospital-acquired pneumonia. Once that cleared, my cough didn’t go away. It lingered and grew worse over time, accompanied by shortness of breath and overwhelming fatigue.

By May 2020, after follow-up imaging, surgical biopsy and evaluation, I was officially diagnosed with pulmonary sarcoidosis. At first, I thought the diagnosis might be another layer of confusion or frustration — another rare condition to navigate. But in reality, it was the beginning of a chapter that would teach me the depth of resilience, self-advocacy, and patience.

Living With Pulmonary Sarcoidosis — The Slow Loss of Air

After our youngest son was born, my body didn’t bounce back the way I expected. Fatigue hit me in waves I hadn’t known were possible. Walking up a flight of stairs left me breathless. Simple exertion became an ordeal. My body, once strong and capable from years of military service and outdoor adventure, now betrayed me in ways I had never imagined.

Hunting trips that had been a source of joy and connection became grueling tests of endurance. I remember one trip in particular — early mornings, scanning the horizon for antelope with my husband. By mid-morning, I was so air-hungry I felt like I might pass out. No matter how deeply I breathed, it wasn’t enough. I had to retreat to the hotel afterward, sleeping until the next day just to recover enough to try again. Some mornings I couldn’t go at all, and on other days I could only hunt in the afternoon.

It was during our last hunting trip in September 2021 that another challenge struck. One moment, I was listening to music and scanning the landscape, and the next, my left ear went suddenly muffled — like the ringing and muffled sensation after a firearm discharge, but there was no firearm discharge and this time there was no relief. My hearing never fully returned.

I immediately did a deep dive into research. I discovered that Gamma Knife radiation can, in rare cases, cause hearing loss. I reached out to the neurosurgeon and radiation oncologist who had performed the procedure and presented my findings. They denied that the surgery could have caused my hearing loss and effectively sent me in the wrong direction.

With surgery ruled out as a likely cause, I moved on to the next possibility: sarcoidosis. But for sarcoidosis to affect hearing, it would have to be neurosarcoidosis, which is far rarer than pulmonary sarcoidosis — essentially highly unlikely. Because there were no visible brain lesions, a biopsy wasn’t possible, leaving my doctors without a clear explanation. Eventually, my sarcoidosis specialists at UCSF diagnosed me with neurosarcoidosis, which led to steroid IV infusions and low dose chemotherapy IV infusions. These infusions temporarily improved my hearing, suggesting that something rheumatological may indeed be affecting my auditory system — though ultimately some of the treatments ended up being unnecessary.

Sarcoidosis’s ability to masquerade as other conditions made this journey even more complex — each symptom could have been explained by something else entirely, which meant I had to rely on meticulous observation, research, and self-advocacy to understand what was really happening in my body.

Around the same time, I was also on prednisone to treat sarcoidosis, which caused rapid weight gain and the classic “moon face,” and I had begun methotrexate, a low-dose chemotherapy medication meant to control inflammation. The combination was brutal. Fatigue became nearly constant. Appetite vanished. Nausea was a daily companion. Within a year of my son’s birthday, I looked at family photos and barely recognized myself — my body had changed despite my efforts to eat well and remain active.

Every day became a balancing act: managing treatment side effects, navigating breathlessness, keeping up with my children, and trying to maintain the life I had known before illness took hold. And yet, even in the fatigue, pain, and frustration, I learned something vital: I was the person who could connect the dots, advocate for myself, and push forward when medical systems couldn’t fully see the whole picture.

Becoming My Own Chronic Disease Manager

Living with multiple rare and overlapping conditions taught me something vital: in many ways, no one else will see your body the way you do. I quickly became my own advocate, researcher, and sometimes even savior.

I have a primary care provider through the VA who is supportive, but in practice, my care often depends on my initiative. I request referrals, track labs, notice urgent changes, and ensure nothing critical slips through the cracks. I see an Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) specialist who oversees my treatment for chronic pain, MCAS, POTS, and hypotension, but I am the one doing the detailed research on my conditions. I come to appointments armed with notes, questions, and observations — often including things that had been missed or overlooked.

My experience as an Air Force medic has been invaluable. It trained me to understand anatomy, physiology, and pathology in a way that most patients never do. Coupled with my autistic special interests — deep, focused study of research and medicine — I can comprehend complex, overlapping conditions and anticipate complications. That combination has quite literally saved my life more than once: from noticing patterns that led to early intervention with my AVM and pulmonary embolisms to advocating for treatments for sarcoidosis before it could cause irreversible damage.

Becoming my own chronic disease manager isn’t just about knowledge. It’s about resilience, persistence, and self-trust. It’s about keeping going when the medical system doesn’t have all the answers, when tests are delayed, and when treatments come with burdensome side effects. Even in the hardest moments — when breathlessness, fatigue, hearing loss, and medication side effects threatened to define my life — I learned that understanding my own body and advocating for it was empowering.

In my view, the Gamma Knife surgery may have been the spark that triggered this cascade of overlapping conditions — a complex interplay of genetics, immune responses, and environmental factors. Recognizing that possibility helped me connect the dots and pursue the most appropriate care, even when conventional medicine offered no clear explanation.

Reflection — What I’ve Learned From My Body

Living through rare and overlapping conditions has taught me lessons no textbook could ever convey. My body has been unpredictable, challenging, and at times frightening. It has pushed me to my limits, forced me to confront vulnerability, and revealed the fragility of life in ways I never anticipated.

And yet, it has also shown me strength — not the kind measured by stamina or endurance alone, but the quiet, persistent kind that comes from knowing your body intimately, trusting your instincts, and advocating fiercely when the system falls short. I have learned that knowledge is power, that research and observation are tools of survival, and that the most effective medicine is often a combination of self-awareness, preparation, and courage.

Sarcoidosis is no joke. Pulmonary sarcoidosis can be life-altering, even life-threatening, and living through its symptoms taught me how quickly health can shift and how crucial timely intervention is. But today, I am profoundly grateful: my sarcoidosis is in remission, my lungs are symptom-free, and I can breathe without limitation — a gift I no longer take for granted.

I have also learned to embrace the unpredictability. My journey — from Gamma Knife surgery to pulmonary embolisms, from an incidental sarcoidosis finding to post-pregnancy chronic illness, from hunting trips that tested every breath to sudden hearing loss — has shown me that life can change in an instant, but so can resilience. Each challenge has shaped me, taught me to adapt, and revealed strengths I didn’t know I had.

Ultimately, this journey is about more than disease. It’s about trust: trust in my own knowledge, my own body, and my capacity to navigate complexity when no one else can. It’s about finding empowerment in the face of uncertainty, and about realizing that even when life becomes unpredictable and exhausting, we can still find ways to live fully, learn deeply, and move forward with hope.

I am no longer just a patient; I am a chronic disease manager, a researcher, an advocate, and a survivor. Through every setback, every unexpected diagnosis, and every day of fatigue and breathlessness, I have discovered that resilience isn’t about returning to who you were — it’s about learning to thrive in the body and the life you have today.

Follow me on YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram for an inside look at my journey navigating rare and complex health conditions, sharing insights from my research and experiences, and connecting with a community that understands the challenges of chronic illness. Join me for personal stories, tips, advocacy, and moments of resilience — and be part of a space where curiosity, knowledge, and support meet.

And as always, Stay Resilient ❤️🩹

Grieving Myself: Living with Dementia as a Young Adult

I’m grieving the person I used to be — the medic, the multitasker, the woman who could remember every detail. After losing my hearing and cognitive function following Gamma Knife radiation, I’ve had to rebuild my identity while living with invisible disabilities the world can’t see. This is my story of autistic burnout, brain injury, and the fight to find purpose in the aftermath.

By Frankie

Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

I’ve been really struggling lately — mentally and physically. My fatigue is worse, my pain is worse, my memory and focus are worse, and even my hearing and ability to process sounds is deteriorating. I’m completely burnt out, and I felt like people needed to hear the real thoughts that constantly plague my mind. I think I’m going into Autistic burnout.

As an Autistic person, I have delayed processing, which means when something happens — happy, sad, or traumatic — I don’t process it at the time. Sometimes it hits minutes later, hours later, days later… or even years later.

The Diagnosis That Changed Everything

I was diagnosed with dementia at 26, but by then, my health had been declining for a few years and I had gone from leading in a high pressure medical environment to being fired for my limitations working as a clinical receptionist... Unfortunately the diagnosis itself fell by the wayside amid the chaos because I simply didn’t have the capacity to fight for it at the time. I was too scared, too tired, too sick.

I lost the version of me who could work, thrive in my special area of interest — medicine. I was sharp, organized, confident. Now, I’m a stay-at-home mom, homeschooling my daughter, and focusing on therapy and medical appointments. I have new purpose — but the grief is still real. Sometimes I wish people understood that losing your hearing or losing your ability to function cognitively feels as if someone has just amputated your arm. I sometimes wish there was a visible sign or indication to prove that yes, I am disabled, but would be insane. I shouldn’t have to prove anything. People should just be more capable of compassion, understanding and empathy. Full stop. Understand us. Accommodate us. Accept US. Just as we accept everyone else.

Coping with Hearing Loss & Cognitive Decline

Along with dementia, I lost my hearing and my ability to process sounds like everyone else. I have to wear hearing aids, and despite using calendars and reminders obsessively, I sometimes show up on the wrong day, at the wrong time, or late.

It’s not just embarrassing — it’s guilt-inducing, because I know my struggles inconvenience others. I’ve always been dependable and punctual, but now I can’t always be the person I used to be.

Phone conversations or any conversation really are extremely difficult because not only do I have hearing loss in both ears so it’s hard to hear on the phone or in a crowded room, I also have auditory processing disorder and memory issues so written communication is honestly the best way to communicate with me if you want me to remember the message you’re trying to get across.

Even on “good” days, I am still sick, still disabled, and still struggling to function in ways most people take for granted.

Anger, Research, and the Medical Response

After my diagnosis, no one cared to investigate the cause of my cognitive changes and hearing loss. I was 26, and no one thought that was alarming so I did what I always do: I hit the research hard.

What I found shocked me: Gamma Knife radiation can cause major neurocognitive disorder (dementia) and hearing loss due to tissue damage. Yet, the medical community refuses to admit it or even investigate it. If I had a confirmed cause, I could accept myself the way I do with my autism. I could explain myself and stop people from assuming, “You just have a lot going on.” This is not the same.

Grieving Myself

I feel like I’m grieving myself — the person I thought I would be. I look back on my military career as a medic and conversations with the doctors I worked with. One of them said, “Sgt, why haven’t you gone to medical school? You’d be an amazing physician.” That memory rips my heart out. I will never be who I wanted to be.

Even as I’m learning to embrace the new me, I am still in deep mourning — a grief so profound I can’t even put it into words. The person I was, the life I imagined, the abilities I had… they’re gone, and some days that loss feels unbearable. It feels like part of me died.

Living with Invisible Disability

What makes this journey almost intolerable is the dismissal from people who say, “Well, you look and sound great!.” While this is not ill intended, it’s harmful because my struggle is invisible. They see a smile and assume I’m fine, but this has been life altering for me.

But I’m still here. I’m still fighting. I’m still showing up — even if no one sees the battles I fight inside. Chronic illness and invisible disability are lonely, but I refuse to stop trying.

Finding Purpose & Resilience

I’m learning, slowly and painfully, to embrace this new version of me. I may not be the person I once was or that I planned on being but I’m still capable of love, resilience, and showing up in my own way. I have a lot to give to the world.

If my story resonates with you — whether you’re navigating chronic illness, brain injury, or invisible disability — you are not alone.

If you don’t live with any of this and are just here to learn then I encourage you to follow me on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram to learn more!

And please, reach out! I love swapping stories and bouncing ideas off of each other to help advocate for our health.

And as always, stay resilient ❤️🩹

Navigating a Complex Diagnosis: My Journey Through Rare Disease, Chronic Illness, and Advocacy

After years of surviving rare conditions, medical errors, and the fallout of life-saving treatment, I’ve learned one truth: sometimes you have to become your own advocate just to stay alive. As a disabled Air Force veteran living with complex chronic illnesses, I use every tool available — including AI — to organize the chaos, tell my story, and fight for better care. This post shares how a missed diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism exposed deeper flaws in the VA system and why trusting your instincts can truly save your life.

By Frankie

Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

Hi, I’m Frankie — I’m 33 years old, a disabled Air Force veteran, and someone living with multiple complex medical conditions. I’m sharing my story not for sympathy, but in hopes of helping others feel seen, advocating for change, and holding space for anyone navigating a healthcare system that doesn’t always listen the first time — or even the tenth.

This blog is my way of organizing the chaos. I use tools like AI and technology to help structure my thoughts, because as someone with autism, ADHD, and a major neurocognitive disorder, communicating clearly and logically has become a real challenge. Masking is something I do well — on the outside, I may look "put together," but beneath that is a network of alarms, calendars, checklists, detailed notes, and the support of my husband.

Today, I want to talk about one of my most urgent health issues — undiagnosed and untreated hyperparathyroidism— and how it slipped through the cracks of the VA system for over two years.

In 2023, the VA flagged elevated calcium levels in my labs and entered a referral for Endocrinology. I had no idea. No call. No message. No follow-up. Nothing. I didn't find out until nearly a year later, when Care in the Community called me to ask if I was ready to move forward with my endocrinology appointment — a referral I never knew existed.

This should have never happened.

In August 2024, I finally had my parathyroid hormone (PTH) level checked — and it was elevated at 87, a result that should have immediately prompted further investigation. I was referred again to Endocrinology, but they declined to see me because my calcium levels looked “normal.”

Here’s what they missed: elevated PTH with normal calcium can indicate Normocalcemic Primary Hyperparathyroidism (NPHPT). It’s real, it’s documented, and it’s serious. But it requires a provider who understands the nuance — and who’s willing to dig deeper.

I’ve become symptomatic. Yes, I have fatigue from Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, but this is different. Since August, my energy levels have dropped sharply. My sleep is unpredictable and fragmented. I now wake between 2–4 AM every day, even when I’m completely exhausted. My go-to sleep supports — including THC — have stopped working.

I'm scared that this will lead to another major flare. I’ve worked too hard to stabilize. I can’t afford to lose access to treatments, especially medications like those for ADHD, which my psychiatrist won’t prescribe if I start losing weight again.

From Air Force Medic to Full-Time Patient

Before I became a full-time patient, I was a medic in the Air Force. For seven years, I thrived in high-pressure medical environments, trained and mentored junior medics, and earned the respect of my colleagues. Medicine wasn’t just a job — it became my language, my special interest, and my safe place as an autistic person.

That experience shaped me into the kind of patient I am today — proactive, hyper-organized, and relentless when it comes to advocating for myself. Not because I think I know more than my doctors, but because I’ve learned the hard way that if I don’t stay on top of every detail, I’ll fall through the cracks.

And I already have.

The Day My Instinct Saved My Life

In early 2019, I underwent Gamma Knife radiation surgery to shrink a massive cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) that carried a 78% lifetime risk of rupture. About a week later, I noticed swelling and pain in my right arm where I’d had an IV. The NP said it was probably just phlebitis. My heart rate was elevated, but they weren't concerned.

Still, something didn’t feel right.

I went to the ER. They found a thrombosis in my basilic vein and a highly elevated D-dimer. A chest CT revealed something terrifying: bilateral pulmonary emboli in all four lobes of my lungs. I was completely asymptomatic. No chest pain. No shortness of breath. Just a gut feeling and a racing heart.

If I had gone home instead of trusting my instinct, I might not be here writing this.

AVM Diagnosis: Another Case of “It’s Probably Nothing”

Backtracking a few months — in late 2018, I began experiencing pulsatile tinnitus, dizziness, and vertigo. It could have been anything. Still, I mentioned to a trusted physician mentor that I’d done some research and wondered about an AVM. He agreed it was worth looking into. He ordered the MRI.

That scan revealed a Spetzler-Martin Grade 5 AVM in my posterior corpus callosum — one of the rarest and most dangerous types. Most people don’t know they have an AVM until it ruptures. Mine didn’t. That MRI may have saved my life.

The Aftermath: Radiation, Hearing Loss, and Cognitive Decline

Within six months of radiation, I lost hearing in my left ear. Within a year, I lost hearing in my right. By two years post-op, I could no longer work due to memory loss, difficulty with cognition, and executive dysfunction.

Eventually, I was diagnosed with Major Neurocognitive Disorder, Autism, ADHD, and a math disability. I'm now under active neurological evaluation to determine whether the Gamma Knife radiation — which research confirms can cause both cognitive decline and hearing loss — is the root cause.

For years, I begged doctors to help me understand what was happening to my brain. They told me it wasn’t serious. That I was overreacting. That it was stress.

It wasn’t.

Layers of Complexity: A Web of Diagnoses

The deeper you go into my medical history, the more tangled it becomes — but each piece matters. Here’s a brief look at the major players:

Cerebral AVM (diagnosed 2018, resected 2024)

Pulmonary Sarcoidosis (diagnosed 2020, in remission with annual PFT follow-ups)

Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (diagnosed 2022)

POTS, Dysautonomia, Orthostatic Hypotension

Gastroparesis, Chronic Nausea

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

Epilepsy Partialis Continua (controlled on Keppra)

Major Neurocognitive Disorder

Autism, ADHD (Inattentive Type), PTSD

Bilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss

Military Sexual Trauma Survivor

I use a central port to self-administer fluids twice per week to stay hydrated and prevent fainting. My medications and therapies are tightly coordinated and managed across multiple specialists.

But even with all of this, my recent experience with hyperparathyroidism shows how easy it is for critical care to be missed.

Where I Am Now — And What I Need

Right now, I need a thorough evaluation of my parathyroid function. I want answers, not assumptions. I want an Endocrinologist who understands that normal calcium doesn’t rule out parathyroid disease. I need someone who will look at my full history, not just a snapshot.

This isn’t just about one lab result. It’s about an entire system that repeatedly fails to see the bigger picture — and patients like me, who don’t fit into neat diagnostic boxes.

Thankfully, I’m still fighting. I have providers who listen. I have a neurologist who’s taking my cognitive issues seriously. I’m hopeful. But I also know that without constant advocacy — from me, from my support system, and from people like you — none of this moves forward.

For Anyone Reading This

Whether you're a fellow chronically ill person, a caregiver, a provider, or just someone trying to understand — thank you for reading. If you take away one thing from this, let it be this:

🟣 Listen to your body.

🟣 Advocate even when you're tired.

🟣 Trust your instincts — they might just save your life.

Stay tuned for a weekly Blog, Mondays at 1500 (3PM MST)

Stay resilient,

Frankie

My Brain Tried to Kill Me: Surviving a Cerebral AVM

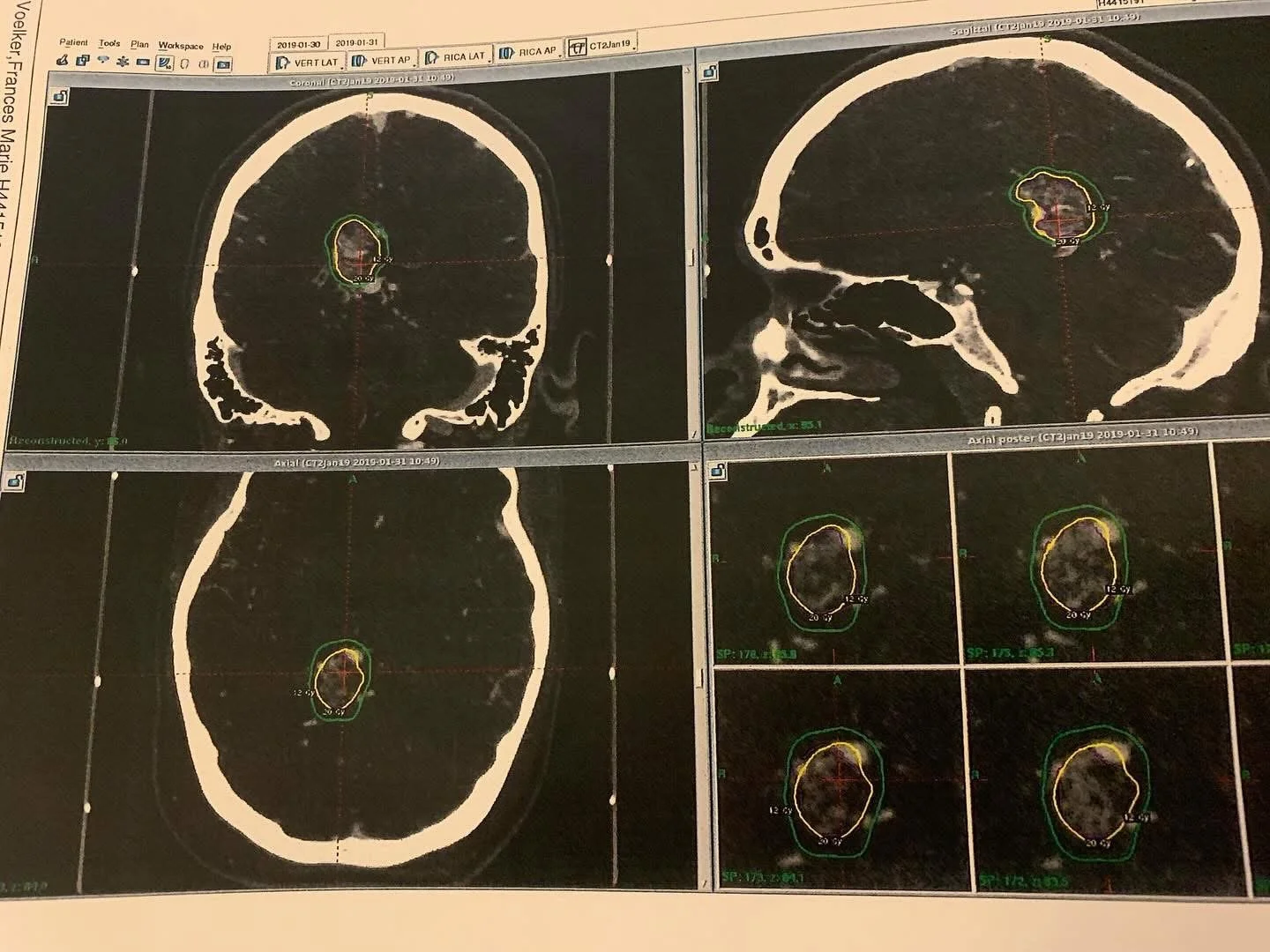

MRI imaging of a cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM), showing a complex nidus of abnormal, tangled blood vessels in the brain. This high-grade (Spetzler-Martin Grade 5) AVM carries a significant risk of rupture, necessitating precise intervention and ongoing monitoring.

By Frankie

Disabled Air Force Veteran | Chronic Illness Advocate | Medical Nerd

Hi, I’m Frankie. I’m a 33-year-old disabled Air Force veteran, and I want to tell you about when I learned I had a cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) — and how it almost killed me before I even knew it was there.

This blog is part of my effort to chronicle my medical history in an honest and empowering way — not just for me, but for anyone living with a complex or rare condition. This is my AVM story, and it starts with a whisper in my ear.

What Is a Cerebral AVM?

A cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a rare and potentially life-threatening condition where blood vessels in the brain form an abnormal connection between arteries and veins, bypassing capillaries. This creates a tangle of fragile vessels prone to rupture.

Occurs in about 0.05% of the population

Can lead to hemorrhagic stroke if ruptured

Often goes undetected until it bleeds

In my case, I was lucky. My AVM was found before it ruptured — but only because I trusted my instincts and had a provider who listened.

Early Symptoms: When Something Feels Off

In 2018, I started noticing subtle but unusual symptoms:

Pulsatile tinnitus in my right ear (a whooshing sound in rhythm with my heartbeat)

Dizziness and episodes of vertigo

A strange sense that something neurologically wasn’t quite right

These symptoms weren’t severe enough to stop me from functioning, but they persisted — and I couldn’t ignore them.

As a trained Air Force medic, I’d developed a habit of digging deeper into symptoms. I started researching differentials, and one condition kept resurfacing: cerebral AVM. It felt unlikely, but my gut told me not to brush it off.

The MRI That Changed My Life

I confided in a physician I respected deeply — a mentor and colleague. I told him about the symptoms and the concerns I had based on my research.

Instead of dismissing me, he listened.

He ordered an MRI.

I went on a family trip to Hawaii shortly after the scan. When I returned, I hadn’t heard anything, so I checked the results myself at work (as I was authorized to do).

And there it was:

“Cerebral arteriovenous malformation.”

I felt the ground shift beneath me.

A Life-Threatening Diagnosis: Grade 5 AVM

Further evaluation revealed the full picture:

Spetzler-Martin Grade 5 AVM (the highest severity level)

Located in the posterior corpus callosum, deep within the brain

Considered inoperable at the time due to size and location

Here’s the part that really drove it home:

The AVM carried an estimated 3% risk of rupture per year, compounded annually since birth — which translated to a 78% lifetime risk of rupture by the time I was diagnosed.

This wasn’t just serious — it was potentially fatal. But I had options.

My team recommended a non-invasive approach first:

Gamma Knife radiation.

Gamma Knife Radiation: Hope and Risk

In January 2019, I underwent Gamma Knife radiosurgery — a focused radiation treatment designed to gradually shrink the AVM and reduce the risk of rupture.